Most people experience back pain at some point in their lives, and it is a leading cause of disability worldwide (1). Back pain can arise from the bones, ligaments or tendons, muscles, or intervertebral discs of the spine. The underlying cause of back pain can be difficult to determine, as many of the potential conditions have similar symptoms. This article discusses the pathophysiology of intervertebral disc conditions and how to differentiate between them.

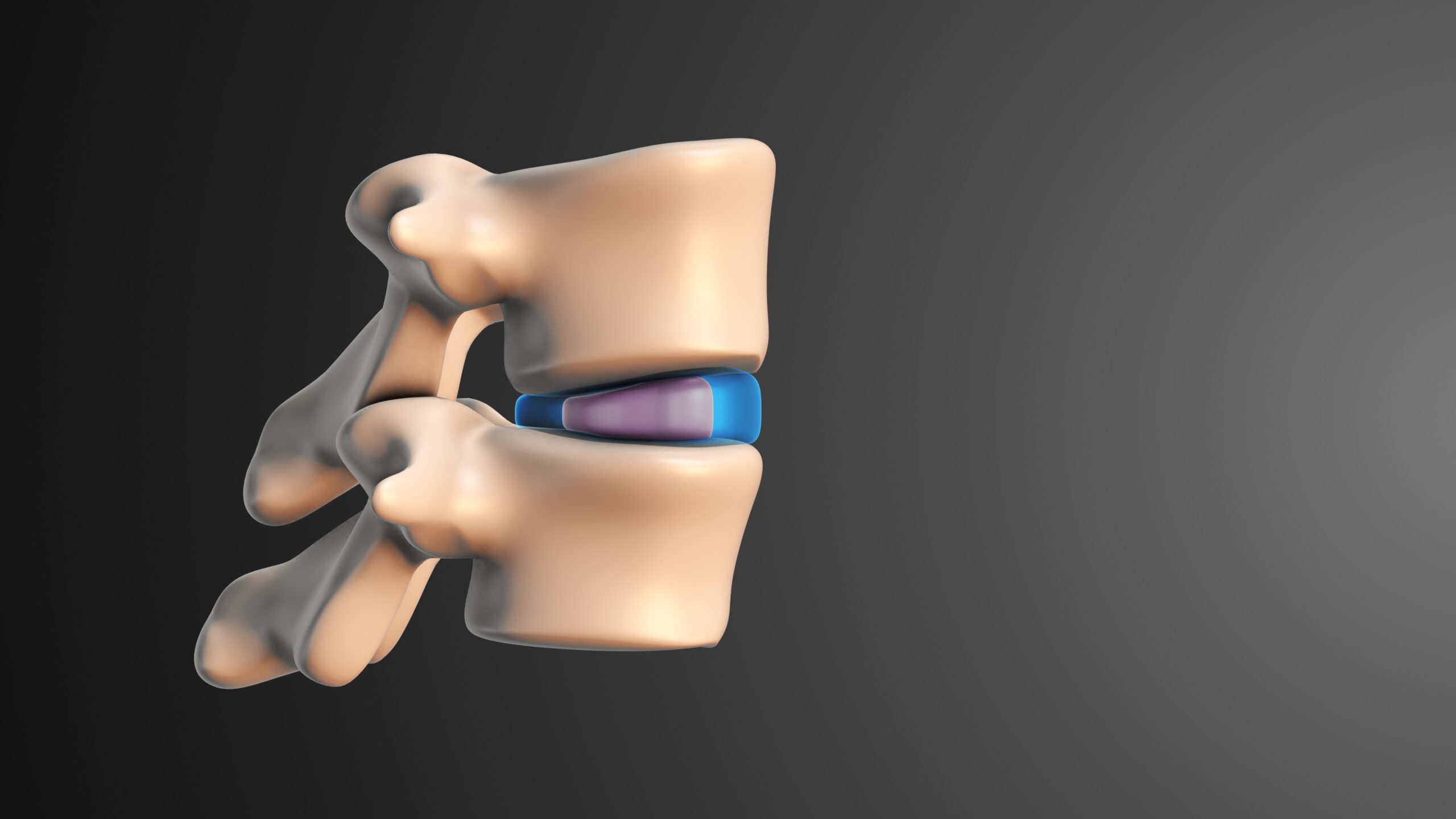

The intervertebral discs are flat, round structures that sit between the bones (vertebrae) of the spine. These discs provide shock absorption to protect the spine, as well as flexibility to allow for spinal movement (1,2). The spine itself protects the spinal cord, which carries almost all motor and sensory signals between the brain and body (3). Each disc has a tough outer ring (the annulus fibrosus) and jelly-like inner ring (the nucleus pulposus) (1,3,4).

One of the common intervertebral disc conditions is intervertebral disc disease, also known as degenerative disc disease or discogenic disease. This condition affects around 5% of Americans each year and is more common among older adults. As its names suggest, intervertebral disc disease is characterized by a gradual breakdown of a disc or multiple discs over time. Research has identified certain genetic variations that increase the chance of experiencing intervertebral disc disease, and other factors have also been hypothesized to have a link, including obesity and driving for long periods of time. Patients experience neck or back pain, depending on where the damaged disc is located. The vertebrae that sandwich the damaged disc can form bone spurs; if these spurs pinch or compress nerves, patients may experience motor impairments and sensory dysfunction, such as pain or tingling, associated with the affected nerve. A weakened disc also has a greater risk of becoming a herniated disc, which will be discussed next (1).

Injury or disease can also cause intervertebral discs to herniate, which is when the inner part of the disc pushes against the outer ring, causing pain. The nucleus may even push fully through the annulus. This condition is also called a bulging, ruptured, or prolapsed disc (1,4). The disc’s ability to properly cushion the spine is impaired, and the herniated area may compress nearby nerves and cause additional issues (radiculopathy) (1,4,5).

This intervertebral disc condition is closely related to intervertebral disc disease – degenerated discs are more likely to herniate (2). However, an acute injury can also cause a herniated disc if the spine experiences too much load or load in an unnatural direction. One cause that is preventable is lifting heavy weights with your back instead of your legs (1,4).

Both conditions can cause back pain and radiculopathy. They can also occur at the same time. In general, diagnosing back pain relies on a thorough history to identify risk factors, a physical exam, and imaging. While disc degeneration cannot be reversed, a herniated disc often improves over time given rest and conservative treatment (1,2,4). Very few patients require surgical intervention (1,4). Other potential causes of back pain may need to be ruled out.

References

- Park, D. K. “Herniated Disk in the Lower Back.” OrthoInfo | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. January 2022. Available: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/herniated-disk-in-the-lower-back/

- “Intervertebral disc disease.” Medline Plus | National Library of Medicine. October 2016. Available: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/intervertebral-disc-disease/

- Healthline Editorial Team. “The Progression of Ankylosing Spondylitis.” Healthline. February 2020. Available: https://www.healthline.com/health/ankylosing-spondylitis/progression

- Mayo Clinic Staff. “Herniated disk.” Mayo Clinic. February 2022. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/herniated-disk/symptoms-causes/syc-20354095

- “Sciatica.” Harvard Health. December 2014. Available: https://www.health.harvard.edu/pain/sciatica