For more than two decades, nerve blocks have been widely used in anesthesia practice [1]. Unlike general anesthesia, regional anesthetic methods allow physicians to targeted specific areas of the body [2]. Given that they also offer significant pain relief over the short- and medium-term, nerve blocks are worth considering in the setting of physical medicine and pain management, both as a treatment option and a method of diagnosis [2].

Nerve blocks are a versatile form of pain management, with demonstrated success in treating a diverse set of conditions across both acute and chronic settings. For example, between continuous supraclavicular nerve blocks and systemic patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), the former produced better postoperative pain control among tip knee and hip replacement patients [1]. This is evident from the 40 to 70% decrease in opioid consumption when PCA is supplemented with a supraclavicular nerve block, as opposed to administered on its own [1].

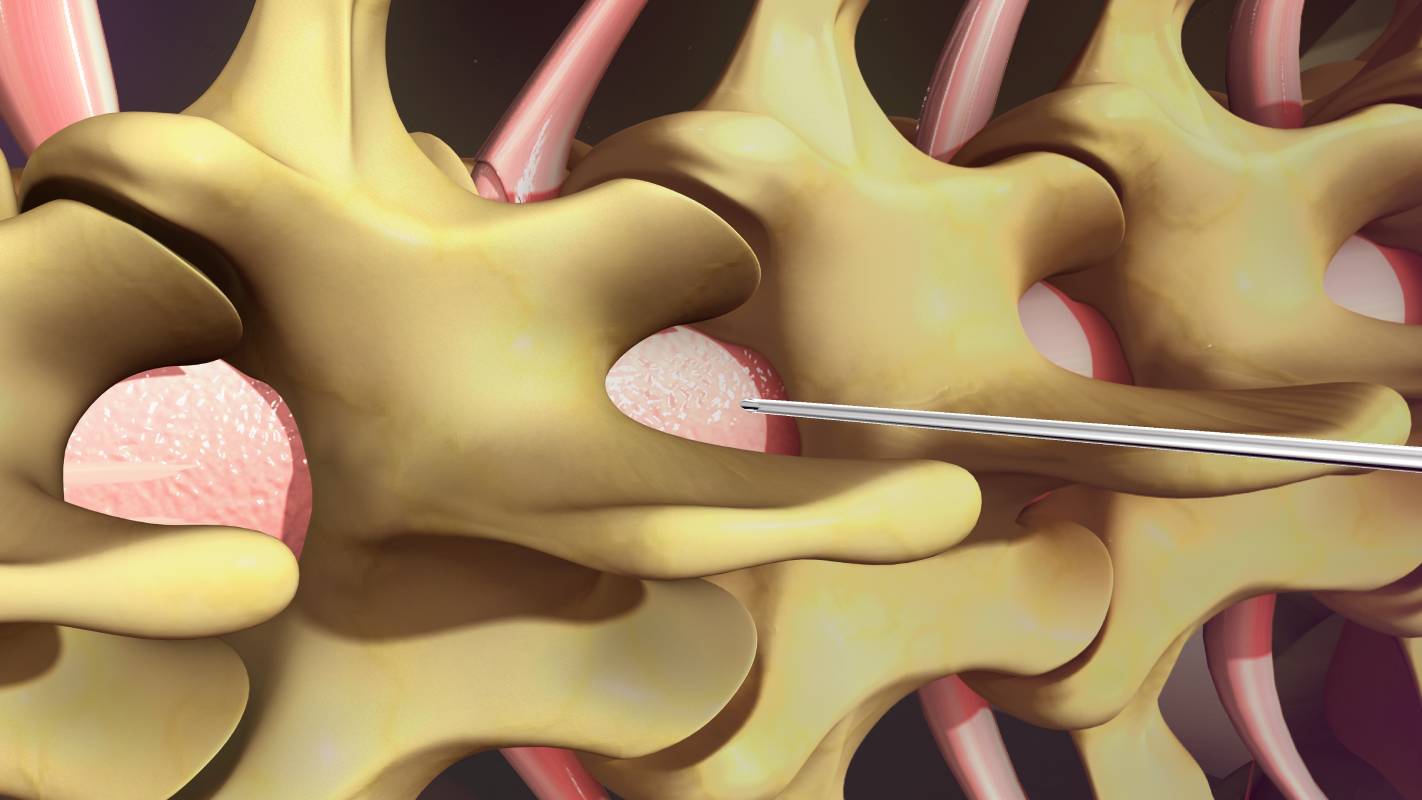

Other forms of nerve blocks, including many newer techniques, are also effective treatment options for certain forms of pain [2, 3]. A prominent example is the ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve block [2]. This technique provides medical teams with improved soft-tissue visualization and real-time needle advancement, increasing the probability of a successful outcome without the tedious trial-and-error previously required [2]. The benefits of this new technique are numerous. Not only are patients relieved from pain, but they also enjoy financial savings and decreased risk of adverse events [2]. Ultrasound-guided blocks have been used in situations ranging from treating headaches, to relieving musculoskeletal pain, to analgesia during surgery [2].

Nerve blocks can also be helpful tools in the context of diagnosing the pathophysiology underlying a patient’s discomfort. Several research studies have centered on the uses of nerve blocks for pain-related diagnosis [4]. For instance, Pampati et al. investigated how effective continuous diagnostic lumbar facet joint nerve blocks were at diagnosing patients who had reported low back pain [5]. They reported that the nerve block contributed to the diagnosis of at least 89.5% of their patients with pain from lumbar facet joint syndrome over two years [5]. Despite this success, it is important to note nerve blocks are not an infallible diagnostic tool: one study suggested that cervical facet joint nerve blocks could have a false positive rate as high as 25.6% when diagnosing cervical spinal pain syndromes [4]. Medical teams should take the chance of inaccuracy into account before depending on this technique.

Before using nerve blocks for either pain management or diagnosis, it is important to be aware of their risks as well. Fortunately, complications associated with multiple forms of nerve blocks tend to be rare [1, 3]. However, they can carry some risk of nerve injury and bleeding [1]. Additionally, given how successful nerve blocks prevent patients from feeling pain in the specified area for a considerable amount of time, the technique can mask the pain from rhabdomyolysis or nerve injury or compression, which could hamper expedient diagnosis [1]. Lastly, infection is possible, albeit rare, when working with a perineural catheter [1]. In the event of infection, the medical team should remove the catheter from the patient’s body and administer appropriate antibiotics [1].

In conclusion, nerve blocks are successful pain management techniques and can also be helpful diagnostic tools. Coupled with their cost-effectiveness and safety, nerve blocks are understandably a powerful technique in physical medicine and rehabilitation.

References

[1] J. E. Chelly, D. Ghisi, and A. Fanelli, “Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in acute pain management,” British Journal of Anaesthesia, vol. 105, no. supp_1, p. i86-i96, December 2010. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeq322.

[2] A. N. Edinoff et al., “Novel Regional Nerve Blocks in Clinical Practice: Evolving Techniques for Pain Management,” Anesthesiology and Pain Management, vol. 11, no. 4, p. 1-8, August 2021. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm.118278.

[3] C. J. Cogan and U. Kandemir, “Role of peripheral nerve block in pain control for the management of acute traumatic orthopaedic injuries in the emergency department: Diagnosis-based treatment guidelines,” Injury, vol. 51, no. 7, p. 1422-1425, July 2020. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2020.04.016.

[4] L. Manchikanti et al., “Assessment of Prevalence of Cervical Facet Joint Pain with Diagnostic Cervical Medial Branch Blocks: Analysis Based on Chronic Pain Model,” Pain Physician, vol. 23, p. 1-10, November/December 2009. [Online]. Available: https://bit.ly/32TZheo.

[5] S. Pampati, K. A. Cash, and L. Manchikanti, “Accuracy of Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: A 2-Year Follow-Up of 152 Patients Diagnosed with Controlled Diagnostic Blocks,” Pain Physician, vol. 12, p. 855-866, September/October 2009. [Online]. Available: https://bit.ly/3gh13ck.